Introduction to BPH

BPH services, by their nature, facilitate a wide array of cyber criminal activities, in- cluding malware distribution, phishing, and botnet command-and-control (C2) operations, due to their deliberate disregard for abuse reports and exploitation of jurisdictional ambiguities [9, 5, 8]. Traditional defences often fall short against their evasive tactics, such as fast flux DNS and Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) [10].

Bullet-Proof Hosting (BPH) serves as a foundational enabler for cyber criminals, providing a se- cure infrastructure that is resistant to take down requests and abuse complaints [10, 9, 8]. This allows malicious content—ranging from phishing pages, malicious code drop-off points and C2 servers to persist online, which continually pose a threat to individuals and organisations [8].

From a technical standpoint, they use a variety of state-of-the-art methods to obscure their operations. This includes frequently changing their IP addresses and domain names, a practice known as ”churning,” which complicates tracking efforts and makes it harder for security teams to build and maintain effective block-lists [14, 12, 7, 5, 8, 9]. Many providers also use proxy services and nested network architectures, often reselling infrastructure from legitimate ”upstream” providers who may be unaware of the malicious activity. This allows them to operate under the cover of a more reputable network [12, 10, 11]. Furthermore, they strategically locate their physical infrastructure in countries with lax cyber-crime laws and weak international legal cooperation [12, 11].

Bulletproof hosting (BPH) serves as the foundational infrastructure for the modern cybercrime economy, providing a "no-questions-asked" sanctuary for malicious activities. Unlike legitimate providers that strictly enforce Terms of Service (ToS) regarding DMCA takedowns and abuse reports, BPH providers intentionally ignore these requests or alert their "tenants" before any action is taken. This allows groups like The Gentleman to maintain persistent Command and Control (C2) nodes and leak sites without fear of immediate suspension.

These providers typically operate in jurisdictions with lax cyber-governance or high levels of corruption, often referred to as "offshore" hosting. By hopping through several international borders, these groups create a legal and technical labyrinth for Western law enforcement. The providers often advertise on dark-web forums, guaranteeing 99.9% uptime for "gray" activities, including phishing landing pages, malware distribution points, and botnet controllers.

Service Models and Tactics

Fast-Flux & Proxy Layers

To remain "bulletproof," modern Russian hosting providers employ Fast-Flux DNS. This technique involves rapidly cycling through hundreds of IP addresses associated with a single domain name, often changing every 180 to 300 seconds. By using a botnet of compromised global devices as "flux agents," the true backend server is never directly exposed. These agents act as a reverse proxy layer, relaying traffic to the "mothership" server hidden deep within a protected Russian ASN.

The use of multi-tier proxy layers further complicates attribution. Sophisticated actors like The Gentleman utilize **Double-Flux** networks, where both the IP address of the target site and the IP of the authoritative DNS nameserver are constantly rotating. This makes standard IP-based blocking entirely ineffective, as the "malicious" IP identified by a defender is often just a compromised home router or IoT device that will be swapped out of the rotation minutes later.

Beyond simple server space, premium BPH groups offer sophisticated "Fast-Flux" DNS services and IP rotation to mask the true location of the backend server. By constantly changing the IP addresses associated with a domain name, they can bypass automated blocking lists and prolong the life of a ransomware negotiation portal. This technical agility is what allows sophisticated actors to remain operational even during active hunt-and-remediate operations by global security firms.

The Ransomware Pipeline

In the specific case of ransomeware groups, such as The Gentleman, BPH is utilized to host the "Wall of Shame" leak sites and the decryption payment gateways. Because these sites must remain accessible to victims to facilitate payment, the hosting must be resilient against Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks and government seizures. The synergy between ransomware developers and bulletproof hosters is symbiotic; the hosters provide the shield, while the developers provide high-revenue, recurring business.

The persistence of these groups into 2026 highlights a significant gap in international cooperation. As long as specific regional hubs continue to provide digital safe havens, the cycle of exfiltration and extortion will continue. Modern defense strategies must therefore focus not just on the malware itself, but on the disruption of the financial and infrastructural lifelines provided by these bulletproof entities.

Key Players

Media Land and the "C3" Nexus

In November 2025, a major international operation targeted Aleksandr Volosovik (known as *Yalishanda*), the operator of the Media Land and ML. Cloud networks. This infrastructure functioned as a primary Command, Control, and Communication (C3) hub for the world’s most dangerous ransomware groups, including LockBit and Black Basta. Operating out of St. Petersburg, Volosovik’s network was the definition of a "bulletproof" shield, providing the dedicated server backbone that allowed these groups to extort billions from Western infrastructure with total impunity.

The "C3" services provided by these Russian hubs are not just technical; they are political. As noted in recent 2026 intelligence logs, these providers operate under "Dark Covenant," where they are allowed to function as long as they do not target Russian interests and occasionally provide "access-as-a-service" to state-aligned entities. This high-level coordination makes the Russian BPH ecosystem the most resilient threat surface in the current landscape.

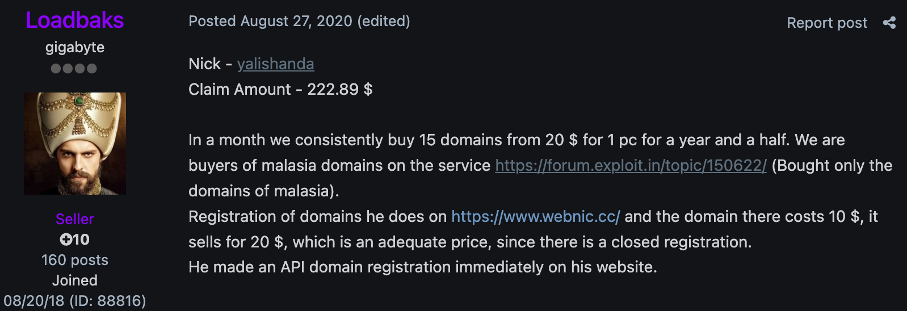

Yashilanda

Some of the most profilic actors inclue, according to Intel471 and others, russian actors including “yalishanda”. Yalishanda" (also known as LARVA-34 or Aleksandr Volosovik) is a prominent, Russian-based bulletproof hosting operator identified as a major enabler of global cybercrime for over a decade. The service provides resilient infrastructure that ignores law enforcement takedown requests, protecting malicious actors involved in ransomware, phishing, and malware distribution.

In November 2025, the UK, US, and Australia sanctioned the Yalishanda-linked infrastructure (specifically Media Land LLC) for supporting large-scale ransomware campaigns, as part of the operation against Dark Convnant.

Whost

M. Mykhailo Rytikov, a russian threat actor who goes by thr names “whost” and “Abdallah” was arrested by the Ukrainian police in 2019, and hosted amongst other things, Jabber servers of the forum Exploit [13].

MikaSweet7 - CloudFlares' largest DoSSer

Recently other infamous BPH providers went dark, possibly because they were affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 [13]. One of them is the BPH “FLOWSPEC”, notably known for providing DDoS protection for major Russian-language cybercrime forums[9]. Another example is “MikaSweet7” who was supposedly able to conduct DDoS attacks that were powerful enough to put offline CloudFlare‘s servers.

Ties to Dark Covnant and Criminal Underground

As reported by Recorded Future in late 2025, the “Dark Covenant” framework [12] describes the web of relationships linking Russia’s cybercriminal underground to elements of the state, especially intelligence and law enforcement services, through a spectrum of direct ties, indirect affiliations, and tacit understandings [12]. The original Dark Covenant report, published on September 9, 2021, argued that these relationships are longstanding and fluid; recruitment of skilled criminals (sometimes under threat of prosecution), selective protection, and the state’s ability to see and shape parts of the underground create an ecosystem in which cybercrime can persist when it serves state interests. Crucially, the report formalized three categories of linkage — direct associations, indirect affiliations, and tacit agreement — and emphasized that the absence of meaningful punitive action often signals tolerance or approval from the Kremlin [12].

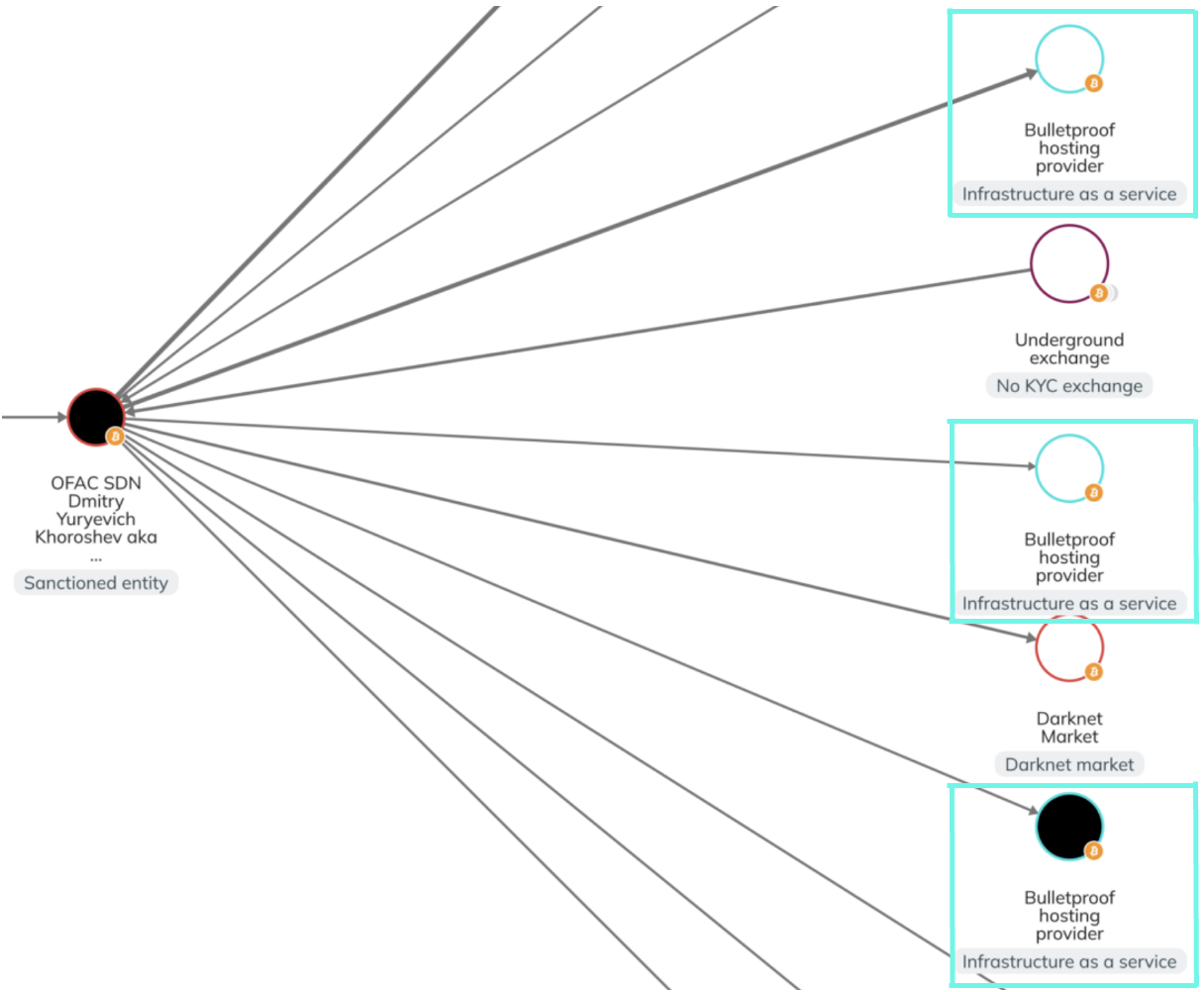

Notably, in May 7, 2024, Operation Cronos culminated in success when law enforcement agencies deanonymized M. Dmitry Khoroshev, the leader of the LockBit ransomware gang. It was aorund this time that other cybersecurity and intelligence companies shared their findings about M. Khoroshev and LockBit’s infrastructure, helping to build a public profile of some of the more famous actors.

Another public case was documented by Chainalysis [13], a company specialising in blockchain analysis, who examined how cryptocurrency transfers from LockBit’s Bitcoin wallets went from other criminal entities, showing the connections between LockBit and, for example, darknet markets, and bulletproof hosting services (BPH). That this single ransomeware group was using at least three (confimred) different BPH providers indicates that bulletproof hosting is a fundamental service in the cybercriminal ecosystem.

Trends

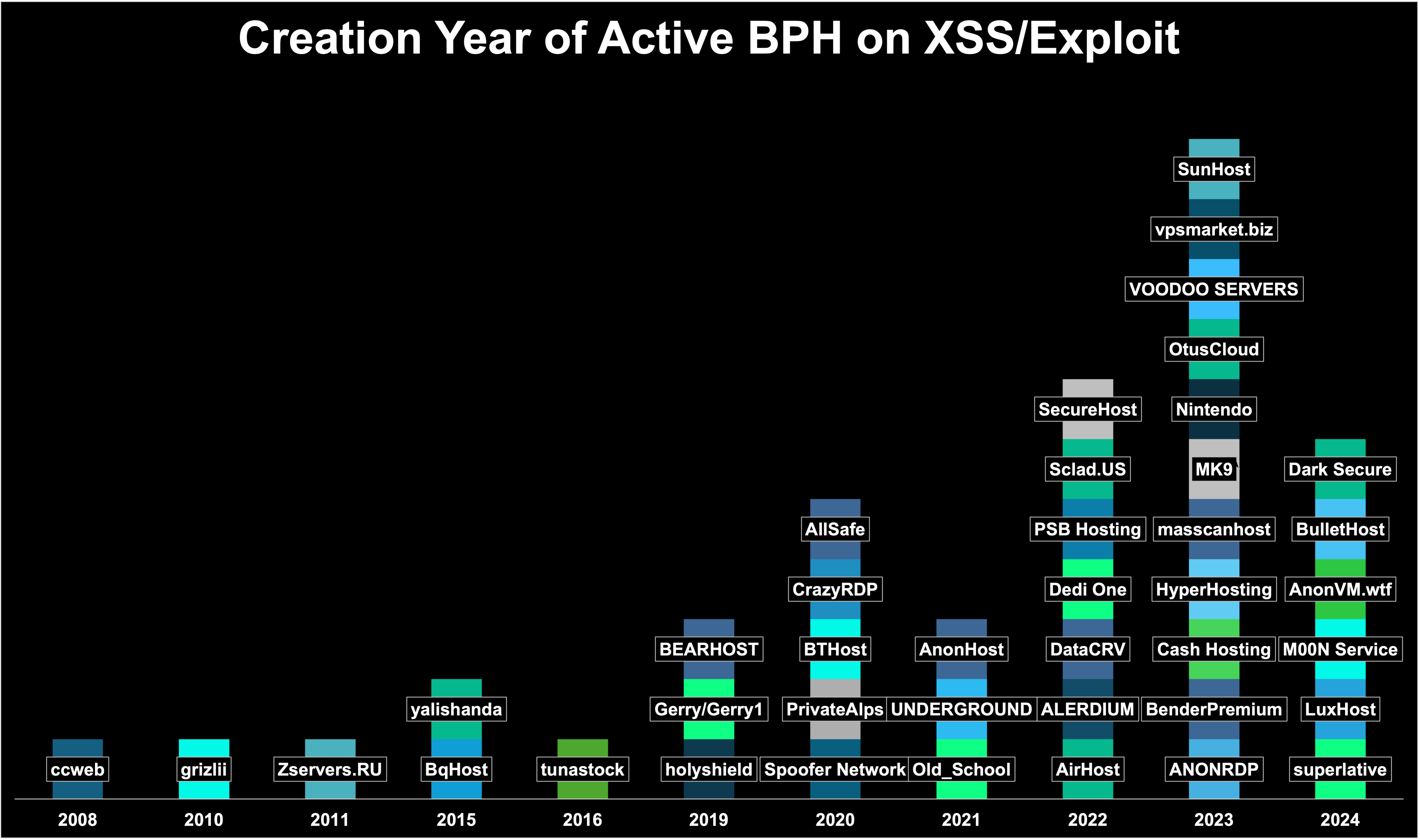

From 2024-2025, security researchers have seen that at least than 17 new BPH services have emerged on the Deep and DarkWeb. Though key big players, such as “ccweb,” “grizlii,” “yalishanda,” and “tunastock” remain active and generally enjoy a positive reputation within the Russian-speaking cybercriminal community, there are a few new players, offering similar services. Though the groups are predominantly Russian, with over 27 recongised as being russian-operated, there are now 13 that have emerged a customer experience to English speaking individuals, potentially filling a gap in the market.

A closer examination of some BPH offers and infrastructures shows that some of them are owned by the same threat groups, but they are split as part of a marketing strategy. Further, there are a few groups that are not operated by the same actors, but still work together to share resources or enhance the quality of their services [13].

A lot of BPHs use sites from Chinese domain registrants, as they are slow to respond to abuse complaints.

Monitoring BPH IP ranges and ASN (Autonomous System Number) reputation is now a critical component of proactive defense. Identifying a new BPH cluster often provides a 48-hour head-start on emerging ransomware campaigns before the first payload is even delivered [13].