Introduction

GoBruteforcer is a modular, Golang-based malware platform designed to compromise Linux-based web servers. It operates primarily as a botnet that spreads via high-volume brute-force attacks against internet-facing services like FTP, MySQL, and phpMyAdmin. Recent variants have integrated "AI-aware" targeting strategies, specifically exploiting the insecure default configurations often found in AI-generated deployment scripts.

Check Point said it identified a more sophisticated version of the Golang malware in mid-2025, packing in a heavily obfuscated IRC bot that's rewritten in the cross-platform programming language, improved persistence mechanisms, process-masking techniques, and dynamic credential lists.

Check Point Research (CPR) observed a GoBruteforcer campaign targeting databases of crypto and blockchain projects. On one compromised host, they recovered Go-based tools, a TRON balance scanner and TRON and BSC “token-sweep” utilities, together a single file containing ~23,000 TRON addresses. On-chain transaction analysis involving the botnet operators’ recipient wallets showed that some of these financially motivated attacks were successful.

The list of credentials includes a combination of common usernames and passwords (e.g., myuser:Abcd@123 or appeaser:admin123456) that can accept remote logins. The choice of these names was determined to be linked to the use of AI to implement databases, as many of them appeared in database tutorials and vendor documentation, all of which have been used to train Large language models (LLMs), causing them to produce code snippets with the same default usernames.

Recent History via Check Point Research paper

Check Point compared the credential list used in GoBruteforcer campaigns against a database of approximately 10 million leaked passwords and found an overlap of roughly 2.44%. This gives us a baseline for a rough upper limit on the number of hosts that might accept one of the passwords that GoBruteforcer has at its disposal: approximately 54.6 thousand MySQL instances and 13.7 thousand PostgreSQL instances (note that this estimate does not account for correct usernames, host-based access restrictions, or other policy controls). Even with a low success rate, the large number of exposed services makes this type of attack an economically-attractive option. Our assumptions are supported by Google’s 2024 Cloud Threat Horizons report, which found that weak or missing credentials accounted for 47.2% of initial access vectors in compromised cloud surfaces. In practice, attackers do not need expensive techniques or zero-day exploits to gain access. They can simply try common usernames and passwords such as admin, 123456 or password1 until they obtain access (the bruteforce model). The evidence shows that this approach still succeeds far too often.

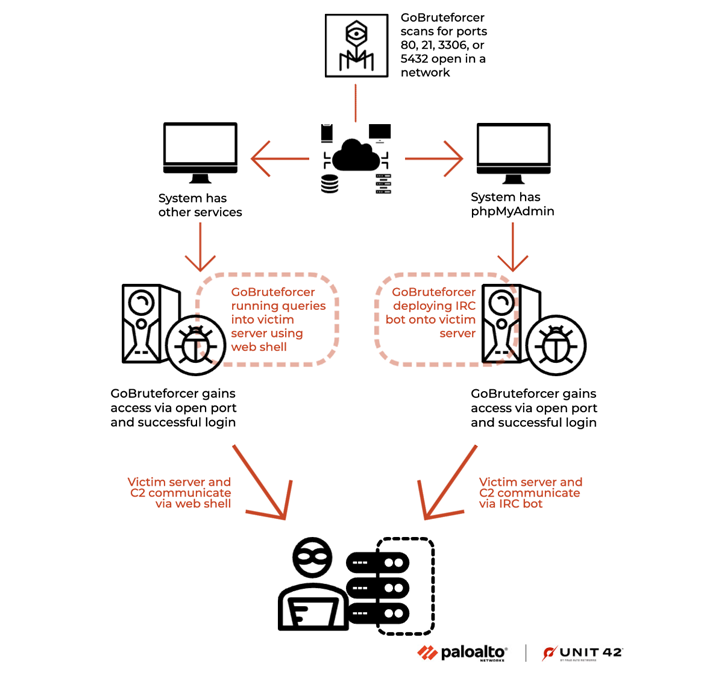

In the activity observed by Check Point, an internet-exposed FTP service on servers running XAMPP is used as an initial access vector to upload a PHP web shell, which is then used to download and execute an updated version of the IRC bot using a shell script based on the system architecture. Once a host is successfully infected, it can serve three different uses:

- Run the brute-force component to attempt password logins for FTP, MySQL, Postgres, and phpMyAdmin across the internet

- Host and serve payloads to other compromised systems,

- Host IRC-style control endpoints or act as a backup command-and-control (C2) for resilience

Victimology and Patterns

GoFroce tends to target Linux-based systems that have poor hygeien or password hardening. They tend to target systems that have been poorly set up or do not have strong authetation methods. For example, their recent victims continue in this trend:

- Initial Discovery (2023): First identified targeting weak FTP and phpMyAdmin credentials on XAMPP-like stacks.

- Evolution (2024):Expanded capabilities to include multiple architectures (x86, x64, ARM), allowing it to infect everything from high-end servers to IoT devices.

- Current Phase (2025-2026):Shifted focus toward "AI-ready" environments, targeting users who deploy servers using LLM-provided boilerplate code without changing default security settings.

The malware has a specific sorting policy when it comes to IP addresses, as most can be pre-skipped due to the following rules:

Private/Non-Internet networks: All RFC1918 private IPv4 ranges are excluded. This covers 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, and 192.168.0.0/16. It also excludes IP addresses in 100.64.0.0/10 (carrier-grade NAT space), the local loopback 127.0.0.0/8, and the non-routed “this network” block 0.0.0.0/8. Similarly, link-local APIPA addresses 169.254.0.0/16 are skipped. None of these are valid targets on the public Internet.

Special reserved ranges: The malware avoids addresses reserved for documentation and testing. For example, it excludes 198.18.0.0/15 (set aside for RFC2544 benchmarking tests). It also broadly filters out multicast ranges by rejecting any address with a first octet ≥ 224 that are not used for regular unicast hosts.

Major cloud provider space: The IP filter also blocks several /8 ranges that are heavily used by Amazon Web Services: 3.0.0.0/8, 15.0.0.0/8, 16.0.0.0/8, 56.0.0.0/8. Cloud environments often have active honeypots and aggressive abuse response; the botnet authors appear to deem these targets as either low-priority or high-risk.

“Sensitive” US government networks: A notable feature is a built-in blacklist of 13 specific /8 blocks historically associated with the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and related agencies. These include IP addresses starting with 6, 7, 11, 21, 22, 26, 28, 29, 30, 33, 55, 214, or 215. Such networks (e.g. 6.0.0.0/8 or 30.0.0.0/8) are largely U.S. military addresses. By skipping them, the bot avoids drawing unnecessary attention and likely sidesteps government-run honeypots and sensors, reducing the chances of the botnet being monitored or disrupted.

Attack Patterns and history

At the same time, the small set of credentials used by the FTP BruteForcer strongly indicates that XAMPP installations are among GoBruteforcer’s intended targets. When attackers obtain access to XAMPP FTP using a standard account (commonly daemon or nobody) and a weak default password, the typical next step is to upload a web shell into the webroot.

To upload a web shell, attackers may also use other vectors, for example, misconfigured MySQL servers or phpMyAdmin panels. Published case studies and write-ups demonstrate practical techniques for achieving code execution or uploading shells through phpMyAdmin when the application or host is misconfigured.

The attackers still use the same PHP web shell that we observed two years earlier (SHA256: de7994277a81cf48f575f7245ec782c82452bb928a55c7fae11c2702cc308b8b). In addition, the samples we observed use the same hashed password for user authentication.

We also suspect the presence of other distribution chains, as we found hosts belonging to the botnet that did not have a web shell installed.

Once GoBruteforcer attackers successfully compromise initial credentials and gain authenticated access to vulnerable services, they rapidly move to establish persistent control by uploading a PHP-based web shell into the compromised server’s web-accessible document root directory. This GoBruteforcer web shell component functions as a remote command execution console, providing operators with the ability to execute arbitrary system commands on the compromised Linux server and prepare the environment for deployment of additional malware stages. The web shell serves as the critical bridgehead that enables GoBruteforcer’s transition from simple authenticated access to full command execution and persistent compromise.

- March 2023 (Unit 42): First documented as a Go-based scanner targeting x86 and ARM.

- September 2025 (Black Lotus Labs/Lumen): Research confirmed that GoBruteforcer and SystemBC share significant infrastructure. Lumen discovered that roughly 80% of compromised nodes were VPS systems, often acting as proxy relays for more sensitive nation-state or high-level criminal traffic.

- January 2026 (Check Point report): Identification of the latest "AI-Aware" variant, which has scaled to over 50,000 active vulnerable targets

General Recommendations

The following is advice coming from several threat intelligence reporting companies, such as Check Point, Trend Micro, Unit 42 and Recorded Future. Overall, they recommend that:

- Sanitize AI Workflows: Implement a policy requiring all AI-generated deployment scripts to undergo a security review, specifically focusing on the removal of default credentials.

- Implement "Identity-First" Access: Transition away from exposing management ports (FTP/MySQL) to the open web. Use Zero Trust Network Access (ZTNA) or VPNs for administrative tasks.

- Egress Filtering: Monitor and block IRC traffic (typically ports 6660-6669) from web servers, as this is a primary indicator of a GoBruteforcer infection.

- Deployment of Honeypots: Set up "low-interaction" traps with default credentials to identify and block the specific IP ranges currently being used by the GoBruteforcer botnet.

IOCs

TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures)

- T1110 (Brute Force): Uses a massive built-in list of credentials, now updated to include common AI-generated defaults.

- T1059.004 (Command and Scripting Interpreter: Unix Shell):Utilizes PHP web shells for initial access and execution.

- T1071.001 (Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols): Uses IRC (Internet Relay Chat) for Command and Control (C2) communication to stay under the radar of traditional HTTP/S monitoring.

- T1027 (Obfuscated Files or Information): Employs the "Garble" tool for Go-specific obfuscation and renames malicious processes to look like system services (e.g., init).

As of January 2026, a new variant has been observed with enhanced Cryptocurrency Sweeping modules. This version no longer just waits for a miner to run; it actively scans databases for TRON and Binance Smart Chain private keys or seed phrases to drain wallets instantly. It has also improved its concurrency, allowing a single infected node to brute-force up to 95 targets simultaneously.